My Grandfather’s Reading Notebook

In the prologue essay in Dinah Lenney‘s collection of essays, The Object Parade, she says, “Things, all kinds–ordinary, extraordinary–tether us, don’t they, to place and people and the past, to feeling and thought, to each other, and ourselves, to some admittedly elusive understanding of the passage of time.” I started a photography project a while ago that I referred to as “Significant Objects” and photographed various objects that had meaning or some significance for me. It was a visual meditation on why we keep certain things or why some things that might seem worthless to others hold significance for us over time. After moving twice in a year, with one move involving a cross-country journey, I had to make many ruthless decisions on what to keep and what to jettison after living in our house in southern California for 17 years, a house that filled up with books and a multitude of other things, rocks, feathers, pens, notebooks…etc. I performed a radical pruning of my book collection, donating close to 100 boxes of books (which barely put a dent in my overall library), keeping the books that meant the most to me. It was a hard exercise, mainly because books are not just objects to me. They are sacred artifacts. They have always been like that for me since I was old enough to read. And that passion for reading was instilled and nurtured by my maternal grandfather, who took me to the library with him every week. He’d walk out with a stack of at least five books and by the time we returned to the library a week later, he had read them all.

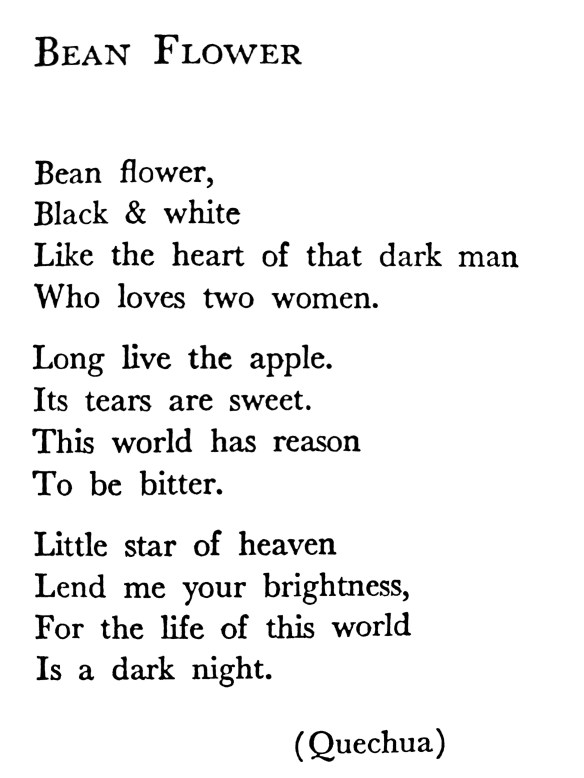

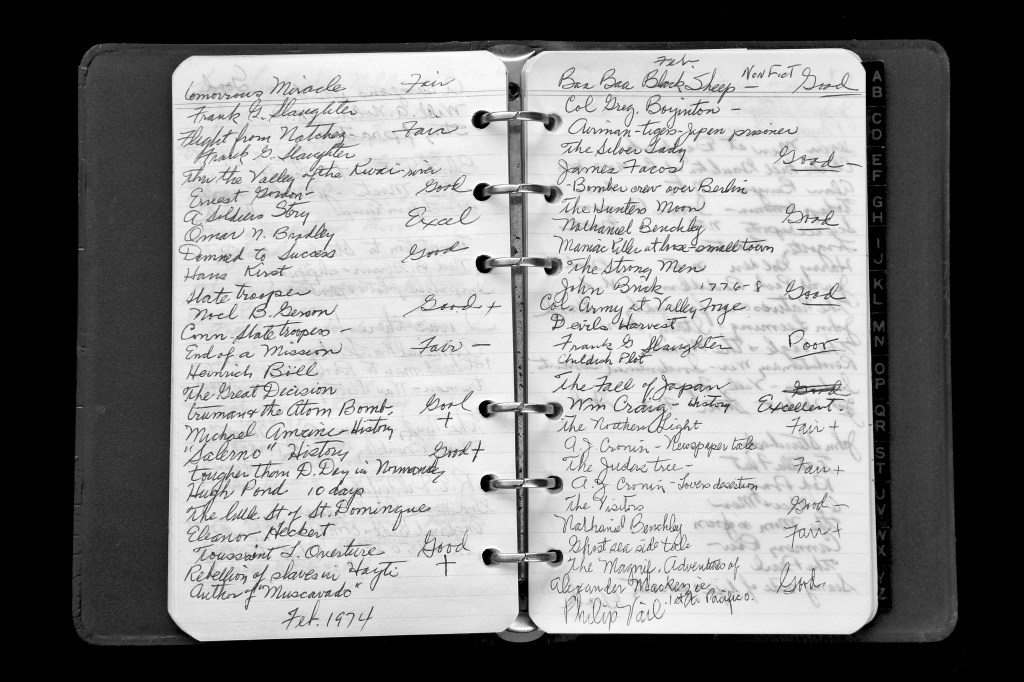

When he and my grandmother passed, my mother and my aunt had to pour through all their belongings to determine what to keep and that’s how my grandfather’s reading notebook, a list of all the books he read from 1971-1974, ended up in my hands along with his library card. At some point, I hoped to incorporate some of the books he read into a reading project of my own, where I have a one-sided dialog with him across space and time about the books he read. He made no lengthy written response about any of the books he read. He simply assigned them a place on a scale of “excellent, good, fair, poor, to very poor.” I, too, keep a reading journal, though I include more information about the books I’ve read than just a grading scale. Still, when I hold my grandfather’s reading notebook in my hands, I can feel his hands, see him jotting down the information about the book he just finished. I was aged 11-14 years old when he kept this notebook (there seemed to be no other reading notebooks, just this one). While he was devouring the historical fiction of Frank G. Slaughter, I was working my way through Madeline L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time series. Time does wrinkle for me as I turn the pages of his notebook. I can still see him sitting at the kitchen table with a book in front of him, a cigar in one hand, and a small glass of whiskey off to one side.